Re-examining the Nature of Fragile X

In the wake of negative results from several high-profile clinical trials in Fragile X, we find ourselves questioning many of our previous assumptions about the nature of this disorder. After all, understanding the basic pathology of disease is critical to development of new treatments — this is true across the board, in all branches of medicine.

In the early days of Fragile X research, shortly after the FMR1 gene was discovered and the normal protein product of the gene (FMRP) was identified, it was noted that FMRP is an RNA binding protein. Whatever the normal function of this single protein which Fragile X patients lack, it had something to do with RNA metabolism. Since RNA is the template used to make new proteins, this meant that the Fragile X protein is involved in regulating protein synthesis.

Work over the next few years led to the mGluR Theory of Fragile X which stated that FMRP normally regulates protein synthesis in dendrites in response to synaptic activity, and that in the absence of FMRP (in Fragile X syndrome) there was abnormal protein synthesis, leading to excessive activity in some signaling pathways.

This theory was extensively validated, pointing to the potential value of mGluR5 antagonists as treatments for Fragile X. But there was always the possibility that this represented only a piece of the puzzle. After all, most biomedical research is done in narrowly-focused model systems; the whole point of using models (animals, cells, etc.) is to simplify the incredibly complex human brain so that experimentation becomes possible. Thousands of experiments by scientists around the world confirmed that absence of FMRP led to consistent signaling abnormalities, and that these could be normalized by decreasing the function of metabotropic glutamate receptors, either genetically or pharmacologically. So, the mGluR Theory isn’t necessarily wrong, but clearly there’s more to the story.

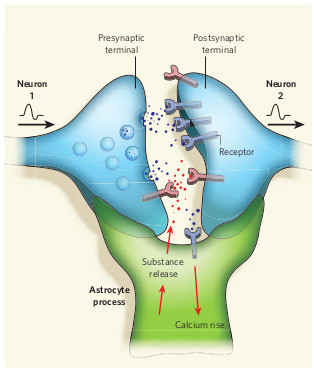

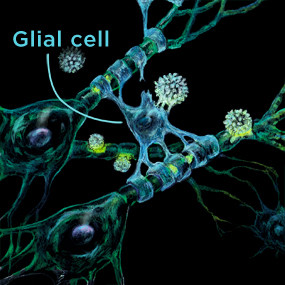

Keep in mind that all of the above takes place in the postsynaptic compartment, otherwise known as the dendrite, or the dendritic spine to be more specific. However, it has been known all along that FMRP is also normally present in the presynaptic compartment, otherwise known as the axon, as well as in surrounding glial cells like astrocytes (these are the non-neurons in the brain that perform many of the household chores.)

So, the question has always been, what’s FMRP doing in all those other places? There’s no protein synthesis in axons, and there’s no synaptic activity in glia, so FMRP must be doing more than just regulating activity-dependent protein synthesis.

Fragile X and Presynaptic Channels: Slack and the Big K

In the years since the conception of the mGluR Theory, valuable clues have come along. For example, FRAXA scientist Dr. Len Kaczmarek of Yale University first found that FMRP interacts directly with certain ion channels to regulate neuronal excitability; specifically, he reported that one section of FMRP (not the RNA binding part) interacts with a large potassium channel called Slack to fine-tune the fidelity of auditory circuits.

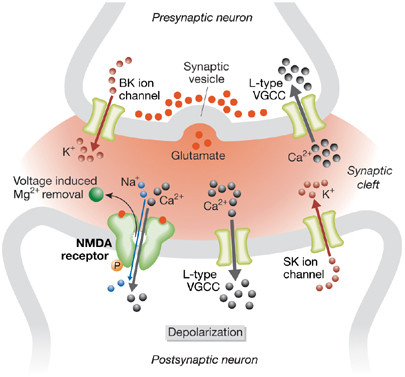

More recently, another FRAXA researcher, Dr. Vitaly Klyachko of Washington University found that FMRP interacts directly with the presynaptic BK channel — literally the Big K (potassium) channel—to regulate neuronal excitability, and that absence of FMRP results directly in hyperexcitability of this system. In collaboration with Dr. Steve Warren of Emory University, the team examined samples from a patient with a rare mutation of FMR1. This patient has a point mutation in the gene, which results in a single amino acid change in the protein, which is produced in normal amounts. The patient has what is described as a “partial Fragile X phenotype” of intellectual disability and seizure disorder, but without the physical features or typical behaviors of Fragile X syndrome.

Examining the protein produced from this mutation, Dr. Klyachko found that it had normal RNA binding properties, resulting in normal activity-dependent protein synthesis and normal mGluR-LTD. The only problem caused by this single amino acid change was that this mutated FMRP could not interact with BK channels, leading to increased excitability of the axon and greater neurotransmitter release. This means there is an entirely separate and distinct presynaptic function of FMRP, not related to its RNA binding function in dendrites. He had found another facet of Fragile X: a distinct presynaptic phenotype unrelated to mGluR5.

Fragile X and Glial Cells

It has long been known that FMRP is highly expressed in the non-neuronal cells of the brain (glia). Additionally, early experiments showed that normal neurons growing with Fragile X glia demonstrated many of the same abnormalities we would expect to see in Fragile X neurons. Conversely, growing Fragile X neurons with normal glia reversed many of the usual structural abnormalities!

Clearly, something is going on in Fragile X glia, and that represents a potentially significant part of the disease mechanism. More recently, FRAXA researcher Dr. Yongjie Yang has shown that Fragile X astrocytes (a type of glial cell) have low levels of a key glutamate transporter, and this deficiency contributes to excessive glutamate levels in the synapse, resulting in hyperexcitability. This abnormality does not respond to mGluR5 antagonists; in fact, they may aggravate the problem. Thus, we have identified key glial phenotypes which appear to be independent of the other phenotypes described in neurons.

As we move forward, we may need to consider the contributions of these distinct presynaptic, postsynaptic, and glial phenotypes to the clinical presentation of Fragile X. We may need to treat them separately for best overall effect, and the knowledge that different things are going on in different places in the brain may help us to develop combination drug strategies which can significantly alter the course of Fragile X.

Further Reading

Glia — more than just brain glue: mcb.berkeley.edu/courses/mcb61/Glia_Nature_Feb09.pdf

New genetic clues found in Fragile X syndrome by Vitaly Klyachko, PhD, and colleagues, Washington University:

news.wustl.edu/news/Pages/27886.aspx and

www.cellbiology.wustl.edu/news/new-publicaton-by-the-klyachko-lab

Written by

Michael Tranfaglia, MD

Medical Director, Treasurer, Co-Founder

Dr. Michael Tranfaglia is Medical Director and Chief Scientific Officer of FRAXA Research Foundation, coordinating the Foundation’s research strategy and working with university and industry scientists to develop new therapeutic agents for Fragile X. He has a BA in Biology from Harvard University and an MD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His son Andy has Fragile X syndrome.